The eerie “whoo-hoo” calls of the Powerful Owl can be heard across the ridges and valleys of our catchment, especially during the evenings and nights of Autumn and Winter when they breed.

These birds hold a special fascination for birdwatchers and the general public because of their large size (Ht. 65cm; Wt 2Kg), their booming calls and their fondness for relatively large prey including possums, sugar gliders, currawongs, magpies, lorikeets and flying foxes.

They also have the peculiar habit of roosting quietly and in complete stillness during the day, with their previous night’s prey dangling from a claw below the branch they have roosted on.

But they are also a species that is classified as “vulnerable” in Queensland.

The magnificent Powerful Owl – © Chris Read

The magnificent Powerful Owl – © Chris Read

For these reasons, Birdlife Australia is conducting a Citizen Science Project to establish numbers, distribution and breeding success of this magnificent bird. The Project Manager is Rob Clements.

The project is only possible because these apex predators are moving into the suburbs of our cities to exploit the numerous prey available. They have become easily detectable by their calls.

It is easy to hear the calls but far from easy to locate the birds themselves, especially if the call is coming from up to half a kilometre away in a very bushy area where they roost and breed!

This is where triangulating can be useful – locating a bird calling at an unknown point by accurately measuring the compass directions from known points A and B.

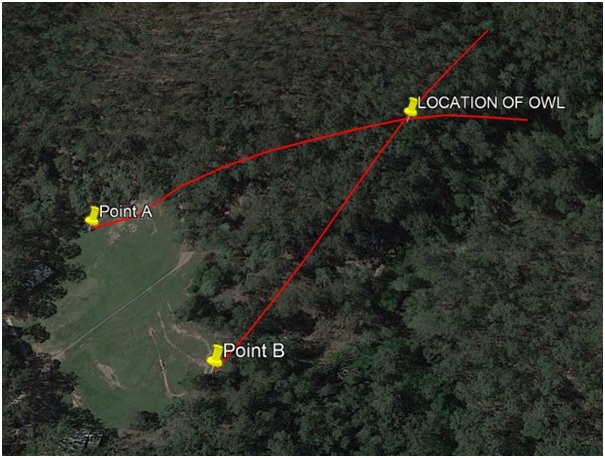

The following Google Earth image shows a hypothetical implementation of the triangulation procedure:

The location in the image is Gap Creek Reserve. It has been used for illustration purposes only. It does NOT show the actual location of a known spot where a Powerful Owl is located.

Triangulation explained

To commence the triangulation process, two birders in phone contact stand at points A and B, which are 97m apart. When each of them simultaneously hear the Powerful Owl call they measure the direction with the compass on their smart phones. A measures the call coming for 73°E and B measures the call coming from 31°NE.

When these measurements are taken home and plotted on Google Earth, they can mark the location of the calling Powerful Owl.

In this illustration the owl was 136m from birder A, and 133m from birder B. The wavy lines plotted on the map follow the terrain and show the “ground length”, the length one would have to walk, climbing the hill to the Powerful Owl point.

The map length is the direct straight length between two points and is not plotted in this image.

How we use triangulation

Local birders Ian Muirhead and Jim Butler know the general location of a breeding pair of Powerful Owls along Moggill Creek from recordings of the owl’s calls at night.

Ian and Jim recorded their calls twice in March, 7 times in April, four times in May, and then they did the triangulation process on 10 June.

Within two days Ian and Jim found the Powerful Owl near the nest hollow on private property, having gained the enthusiastic cooperation of the land holder.

Since that time they have visited the nest site on a number of occasions.

On a day during the second week of August Ian and Jim were near the nest at 5:30pm. They saw the female first as she arrived at the “butchery” tree roost.

Minutes later the male landed beside her with a fruit bat dangling from its claw. The male then proceeded to rip the bat apart and feed sections to the female, beak to beak. After about ten exchanges, the female flew to the nest hollow and Ian and Jim could hear the chick trilling as it was fed.

Like to learn more?

If you would like to receive a recording of the Powerful Owl call by email, and/or you can hear Powerful Owls in our catchment and would like to contribute to the Citizen Science Powerful Owl Project, please contact Jim Butler at [email protected]